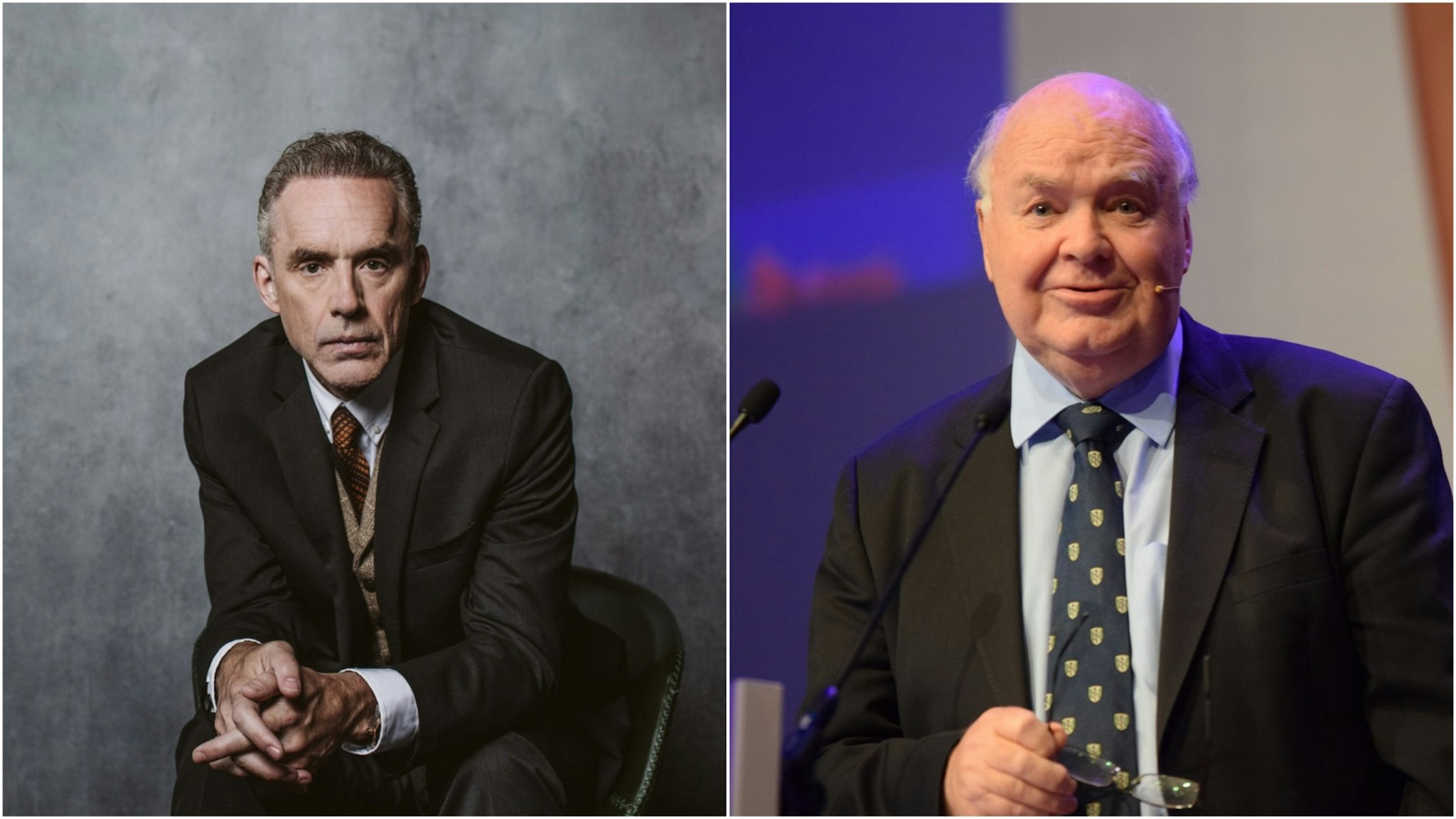

The following is a transcript excerpt from Dr. Jordan Peterson’s conversation with Dr. John Lennox on Nietzsche’s seventeenth-century prophetic observation, the eternal voice of being, the concept of transcendence, the glory and weight of being, and Jesus Christ’s triumph over death. You can listen to or watch the full podcast episode on DailyWire+.

Start time: 36:16

Jordan Peterson: In the late 1800s, Nietzsche observed that God was dead. It was a very complex observation because people like to think of that as a triumphalist proclamation by this emancipatory philosopher. But that wasn’t the case at all because Nietzsche basically said that God was dead, we had killed him, and we will never find enough water to wash away the blood. He knew it was a catastrophe, and he prophesied that three things would happen. One was that there would be a wicked turn toward a kind of hopeless nihilism because every structure of morality had fallen apart. The second was the rise of totalitarian substitutions for God; Nietzsche actually specified communism as a likely candidate and also prophesied that hundreds of millions of people would die as a consequence, which was quite the damned prophecy for the mid-late 1800s. Then he also said the alternative is that we could create our own values. And that was the root that Nietzsche saw as the way out.

Now, there are a couple of technical problems with that, you might say. One is that we don’t live very long, and it is not obvious that any of us are wise enough to create our own values. The second problem is, as the psychoanalysts pointed out very quickly, it is not obvious at all that we are masters in our own houses because even if you only look at the spiritual realm as equivalent to something like the unconscious, we are all haunted beings — and we cannot necessarily trust our judgment.

Therefore, the third problem is, who do you mean by the “we” who will create our own values? Which aspect of the psyche is now going to create value? Nietzsche said himself that each drive tends to philosophize in its own spirit, so in order for us to create our own values in some sort of transcendent sense, you have to hypothesize the hierarchical integration of the psyche towards some super ordinate end that is speaking in some voice. And it is not obvious to me at all that that would be a subjective voice.

So when Moses investigates the Burning Bush, he goes deeper and deeper into the investigation, and the first thing that happens is, his attention is attracted. The second thing is that he starts to notice that he is treading on sacred ground because he is getting deep into the phenomenon. The third thing that happens — and this is relevant to your notion of levels of revelation — is that the voice of being itself speaks to him. The eternal, transcendent voice of being. Moses is smart and wise enough to know that that is not him. It is something above and beyond him, and he does not take credit for it. That is partly why he never turns into a pharaoh in the desert. He separates himself from the source of sovereignty as such, and I do not see how that can be done in the rationalist, atheist, materialist realm of conceptualization. You fall into that subjectivist trap.

WATCH: The Jordan B. Peterson Podcast on DailyWire+

John Lennox: Nor do I, and I think nature in that sense was a kind of prophet. And we’re seeing the damage done. You know, ever since I was very young, I was fascinated by the polar opposite of my Christian heritage. That has led me to spend quite a lot of time in Russia and I’ve talked about these kinds of things to Russian friends, many of whom suffered in the Gulag. I remember one conversation with a leading academician and he said to me, “You know, John, we thought we could get rid of God and retain a value for human beings. And we woke up too late to realize that it cannot be done.” It was nature that said if you destroy God, you lose all right to the kind of values that we accept, in a sense, deep down in our Judeo-Christian culture. What is so interesting about Moses — and I loved your discussion about that — is that he came face to face not only with the concept of transcendence, but transcendence itself. He was brought into the presence of the very glory of God.

You were discussing in your round table how in Hebrew, glory is associated with weight, and that leads me to think, relevant to what you’ve just said, about C.S. Lewis. I’m old enough to have listened to C.S. Lewis, by the way, when I was younger. C.S. Lewis in the 1940s saw exactly what was going to happen if a group of human beings took it into their heads to determine and redefine all future generations through genetic experimentation and so on. And in two books, “The Abolition of Man” and “That Hideous Strength,” he spelled that out, and he made the point that if that happens, it is not going to liberate human beings. In fact, it’s going to abolish them because what would be created by, say, playing around with the germline, is not human beings but artifacts. So he writes [in] the final triumph of humanity, scientists will be the abolition of man. It’s that that I fear is really permeating our culture. I mean, the Caesars in Rome and the Babylonian emperors who thought of themselves as gods looks pretty trivial compared with this insidious teaching that’s around in particularly the Western world today, that we are actually all gods, that we ought to rise to this, and the only way to rise to it is to reject the transcendent completely; there is nothing above us.

Jordan Peterson: Let’s delve into that a little bit because the devil’s always in the details. When I had little kids, I thought about there being a terrible fragility to children. Adults are fragile too, obviously. We all are because we are mortal and vulnerable and prone to suffering. But I thought about my three-year-old son; he has this terrible vulnerability. Wouldn’t it be good if that could be ameliorated? You can do that two ways: You can institute protective mechanisms that shield them from the depredations of the world or you can strive to make them into the sort of competent people who can take the world on their own. This is akin to the gospel ideas, I would say, that you can learn to handle serpents, and that is your best defense against serpents. That way you get to have the benefits of being and develop into someone simultaneously capable of bearing the weight of being, let’s say. And I do not know if you can have being without it having a weight. I do not even know. It is like it is possible that mortal limitation is the price you pay for being. I do not know how things are constructed.

John Lennox: It could well be. What you are saying reminds me of Dostoyevsky, who said that he couldn’t imagine a great person who had not known some kind of suffering. What we try to do with our children is somehow to limit that, but we realized that part of their maturing has to do with how they learn to handle life and we don’t want to leave them defenseless, do we? So what you’re raising is a very big set of questions.

Now, you mentioned that transhumanism attempts to solve some of this vulnerability and, of course, some things are very good. I wear glasses, and they enhance my vision and they’re very important. But this idea of Harari’s where he sets two agenda items for the 21st century — firstly to abolish physical death, to solve that as a tactical medical problem, and then to enhance human happiness by genetic engineering and cyborg engineering and so forth — I take a very radical view of that. When people hold out this promise to me, I simply say to them, “You’re too late.”

The problem of physical death was solved 20 centuries ago because I think there is strong evidence that Jesus Christ rose from the dead. And the problem, therefore, of developing some kind of immortality was simultaneously sold to that because Christ promises to those that trust him and follow him that he will eventually raise them from the dead, and that will be the best uploading you can ever imagine of brains, body, and everything else. So I take a very radical view that the transhumanist ideal is bound to fail and there’s deeper reasons behind that as well.

* * *

To hear the rest of the conversation, continue by listening or watching this episode on DailyWire+.

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson is a clinical psychologist and professor emeritus at the University of Toronto. From 1993 to 1998 he served as assistant and then associate professor of psychology at Harvard. He is the international bestselling author of Maps of Meaning, 12 Rules For Life, and Beyond Order. You can now listen to or watch his popular lectures on DailyWire+.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?