“The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot” on June 19, 1944, was the most lopsided aerial victory of the Pacific War. In one day Japan’s 1st Mobile Fleet and land-based contingent lost over 300 aircraft and crew, rendering Japanese naval air power a shell of the fighting force that had so confidently sallied forth to meet the Americans and end the Saipan invasion.

Admiral Ozawa, however, still commanded a formidable array of surface ships. And although U.S. submarines had sent two of his three prized fleet carriers to the bottom, he was still eager for a fight with the seven carriers and roughly 150 planes he had remaining, plus aircraft he mistakenly believed were still in some force on Guam, which was not the case. He’d planned on rendezvousing with his tankers, refueling, and hitting the Americans again in the morning.

But his opposing tactical commander, Admiral Mitscher, refused to just sit back and wait to be attacked again. He wanted to pursue and destroy the Japanese fleet. There was, however, a problem. The Americans weren’t sure where Ozawa’s ships even were. Throughout the day, U.S. scout planes scoured the vast emptiness of the Philippine Sea in a desperate search to locate the Japanese fleet.

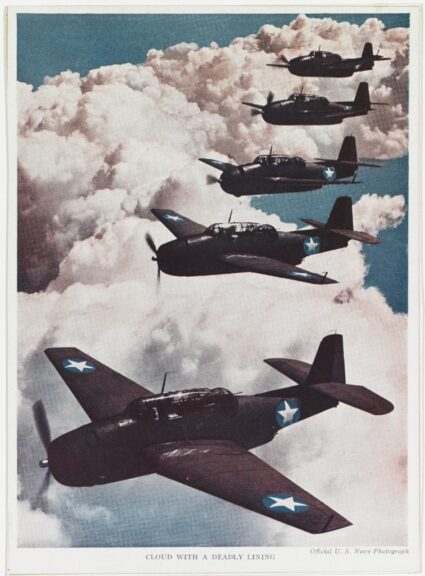

It wasn’t until 3:15 in the afternoon, and after flying some 300 miles, that a scouting party from Enterprise flying Grumman Avenger torpedo planes spotted the unmistakable pagoda-like masts of the Japanese fleet and radioed their find to Task Force 58.

Grumman “Avenger” Torpedo Planes fly in formation, circa 1942-1944. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Listeners aboard the cruiser Atago intercepted the Americans’ transmission and informed Ozawa. Realizing 1st Mobile Fleet had been spotted, the Japanese commander ceased the refueling operation and ordered the fleet to sail northwest at 24 knots, away from the Americans.

Due to delays in deciphering, the sighting didn’t reach Mitscher on board his flagship Lexington until 4:05 p.m. Now the physically frail but aggressive admiral faced an agonizing decision. The scouts’ report showed the Japanese fleet to be some 275 miles away. This was the very limit of his attack aircraft’s range. And to make matters worse, he had only four hours of daylight left to work with. This meant that he’d have to recover any potential strike in darkness, and few of his aircrew were trained in night operations. What should he do?

Vice Admiral Marc A. Mitscher aboard USS LEXINGTON (CV-16) during The Battle of The Philippine Sea, 19 June 1944. National Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command.

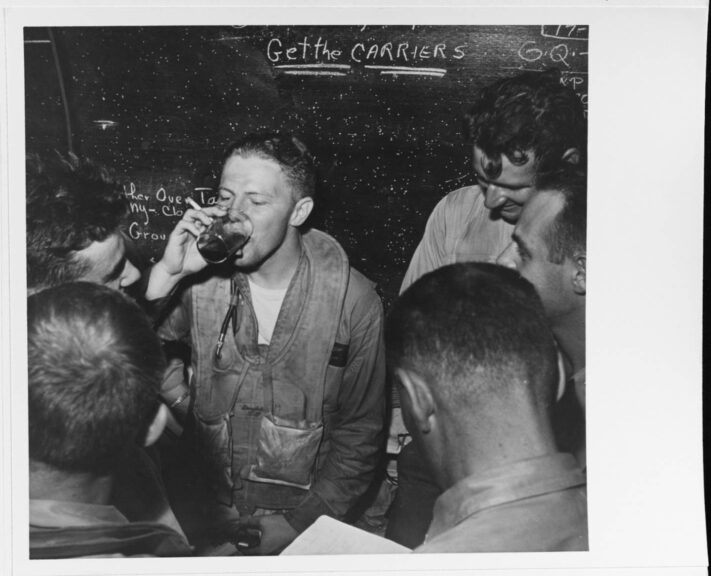

After a few minutes of reflection, Mitscher concluded the Japanese carriers were just too tempting a target to let slip away. He ordered his staff to “Launch the first deckload as soon as possible. Get the carriers!”

When the aircrews who’d been anxiously waiting below decks all day received their orders, they knew what this meant for them; they resigned themselves to flying a dangerous mission at the maximum range, followed by possibly having to ditch in the pitch blackness of the Philippine Sea’s shark-infested waters when their tanks ran dry. Even if they did make it back, how would they find their carriers observing blackout protocol in what was a moonless night on the open ocean? Without hesitation they scrambled to their waiting aircraft across eleven carriers and sped down the flight decks, heading west, unsure what the enemy warships, and a setting sun, had in store for them.

Photographed by Lieutenant Victor Jorgensen, USNR. Official U.S. Navy Photo. National Archives.

Navy Cross recipient, Lt. Harold Buell, piloting a Curtiss Helldiver bomber, recalled:

I have always thought that the most amazing thing about this mission was that it ever took place at all. Almost all the pilots leaving the carriers…knew they were going beyond normal gas range to hit the enemy. If the Japanese had launched such a strike against our fleet we would dub it a suicide mission. Yet, almost to a man, we went on the mission as ordered.

Suicidal or not, a strike package of 240 planes headed for the enemy flotilla.

Battle of The Philippine Sea, June 1944. TBFs and SB2Cs enroute to attack the enemy. National Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command.

After a two-hour flight, the cloud of American aircraft caught up with Ozawa’s fleet. 95 Hellcats ripped through the Japanese combat air patrol to clear the way for the dive bombers and torpedo planes. In the ensuing dogfight, 65 more of Osawa’s aircraft were sent flaming into the sea. With the skies cleared of enemy fighters, the attack aircraft dispersed to hit as many of the seven aircraft carriers at the center of the Japanese strike force as they could.

The anti-aircraft was ferocious, however, and several U.S. planes were blown out of the sky. Buell likened it to “diving into an Iowa plains hailstorm.” While dive bombers pitched over from 10,000 feet and screamed down to drop their payloads, torpedo planes skimmed the waves, frothing with enemy shells and bullets, to release their fish and send them towards their intended targets.

In the ensuing attack, the Americans mortally wounded two oilers and the fleet carrier Hiyō, while rocking three other light carriers with non-fatal bomb and torpedo hits. It had not been the knock-out blow that Mitscher had envisioned. Still, the losses inflicted by the determined U.S. air strike along with the mauling his own air wing had suffered over the last two days convinced Ozawa to abandon any further operations to disrupt the landings on Saipan.

But for the American fliers winging away to the east and darkness, and many planes battle damaged, their struggle was just beginning. They had some 300 miles between them and their own carriers, and not a drop of fuel to spare. Many planes were also battle damaged, making their journey home even more perilous. Not to mention several men were painfully wounded. Would they make it back to their carriers? Or would hundreds of Task Force 58’s aircraft and, more important, their highly trained and brave crews, run out of gas and be compelled to ditch and be swallowed up in the unforgiving vastness of the Pacific?

Battle of The Philippine Sea, June 1944. Japanese plane crashes during a night attack on TG 58.3, 19 June 1944. Seen from USS LEXINGTON (CV-16). National Archives. Naval History and Heritage Command.

They headed east into what was soon pitch darkness, without even moonlight to guide pilots relying on navigation alone to get them home. It wasn’t long before scores of U.S. planes with empty tanks began belly-landing into the sea. In the eerie night time the airwaves filled with panicked voices breaking radio silence to announce they were out of fuel and ditching into the forbidding black waters of the Pacific.

Another Navy Cross recipient, LCDR Ralph Weymouth, while flying an SBD Dauntless dive-bomber off the Lexington, remembered:

At one time so many people were talking on the radio I finally turned it off. I just couldn’t stand hearing these guys saying ‘How much gas have you got left?’ ‘I’m going in shortly.’ ‘I’ve got two minutes left.’ That sort of thing.

After two hours of dead reckoning towards their task force, the desperate Americans weren’t sure where their ships were. They gazed down through their canopies into an eerie dark emptiness. All seemed lost.

And then Mitscher, a flier himself who loved his airmen like a father, made one of the bravest decisions of the war: He ordered all the lights of the fleet illuminated, fired brightly burning star shells, and sent spotlights crisscrossing the dark tropical sky. Considering this would announced their location to any Japanese submarine in the vicinity, it was a remarkable decision. The surviving planes began to land as best they could or belly into the water next to their ships if too heavily battle-damaged or when their tanks finally ran dry.

Over the subsequent days, Mitscher’s ships searched far and wide to try and recover as many floating airmen as they could. Although the battle cost the lives of 49 aviators, amazingly, over the course of the week, 160 water-logged fliers were fished out of the water. Mitscher would be revered for risking his ships to rescue his airmen rather than abandoning them to die a lonely, torturously slow death bobbing in the open ocean.

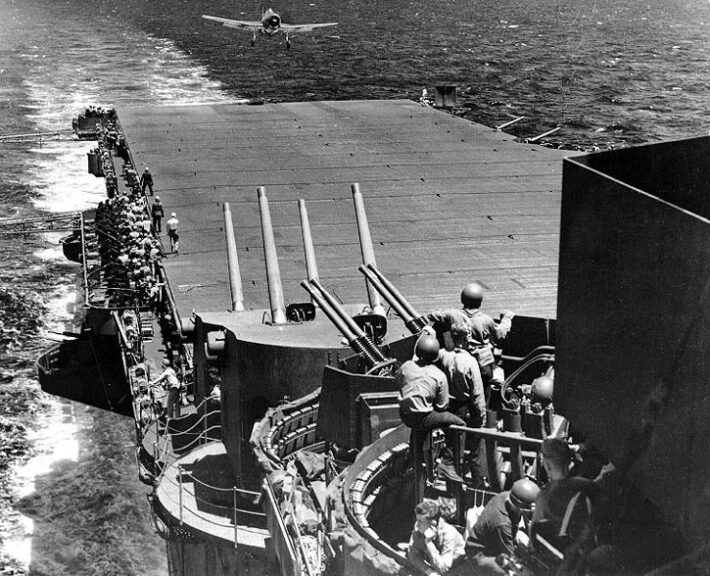

USS Lexington during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, June 1944. US Navy. Wikimedia Commons.

The raid on June 20, 1944, and subsequent perilous return trip, would be remembered as the “Mission Beyond Darkness.”

The two-day Battle of the Philippine Sea cost the Americans relatively little compared to the Japanese who lost three fleet carriers, three oilers, and over 3,000 sailors and airmen killed in action or lost at sea, including over 600 pilots.

In two days, the U.S. Navy rendered Japanese naval air power impotent. Still, many on Task Force 58 fumed that the hesitant Spruance, by not immediately attacking the Japanese ships when first sighted, had denied them an even greater victory. For his part, however, Spruance saw his primary mission as protecting the landings, not chasing after enemy carriers. Especially when they could have been a decoy — a tactic the Japanese would actually use to lure the aggressive “Bull” Halsey into abandoning the landings at Leyte four months later, nearly dooming MacArthur’s Philippines reconquest.

Regardless, the battle at sea was over, but the bloody fighting on Saipan raged on.

* * *

RELATED: The Battle Of Saipan, Part One: Invasion

RELATED: The Battle Of Saipan, Part Two: The Great Marianas Turkey Shoot

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities trader, columnist, and author of two acclaimed novels. Along with Daily Wire, his articles have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, New York Daily News, New York Post, National Review, The Federalist, The Hill and other media outlets. His newest book, LIFE IN THE PITS: My Time as a Trader on the Rough-and-Tumble Exchange Floors, is a fun and informative memoir of his time as a floor trader in Chicago and New York. You can also find more of Brad’s articles on Substack.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?