It was the most powerful amphibious armada of the Pacific War thus far. The task force consisted of 535 ships of the U.S. Fifth Fleet ferrying 127,000 personnel, which included some 70,000 landing troops of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions ready to storm the beaches, along with the Army’s 27th Infantry Division in reserve; these formations combined made up the Fifth Amphibious Corps.

For two days prior, an ever-growing number of U.S. Navy battleships, cruisers, and destroyers mercilessly shelled the island of Saipan in the Central Pacific, second largest in the 500-mile long Marianas Islands chain. At dawn on June 15, 1944, D-Day, the shore bombardment resumed as the warships leveled their guns and opened up on the beaches and lush green hills beyond, into the presumed Japanese positions, to clear the way for the landing force.

Ship of task force 52 prepare to depart Roi for Saipan, 12 June 1944. Seen from NEW MEXICO These ships are (left to right): USS McNAIR (DD-679); USS MONTPELIER (CL-57); USS HONOLULU (CL-48); USS TENNESSEE (BB-43). Catalog #: 80-G-253678. National Archives. Courtesy: Naval History and Heritage Command.

Saipan is roughly twelve miles long and five miles wide; from the air it looks somewhat like a long-necked dinosaur. In reality, it is a beautiful island with a landscape that varies from sandy beaches and a coral-reefed lagoon to sugar cane fields and forbidding limestone escarpments rising to the peak of the 1,560-foot high Mount Tapochau. It was not the enticing blue waters and colorful flora of the Marianas that attracted the Americans; rather it was its strategic location.

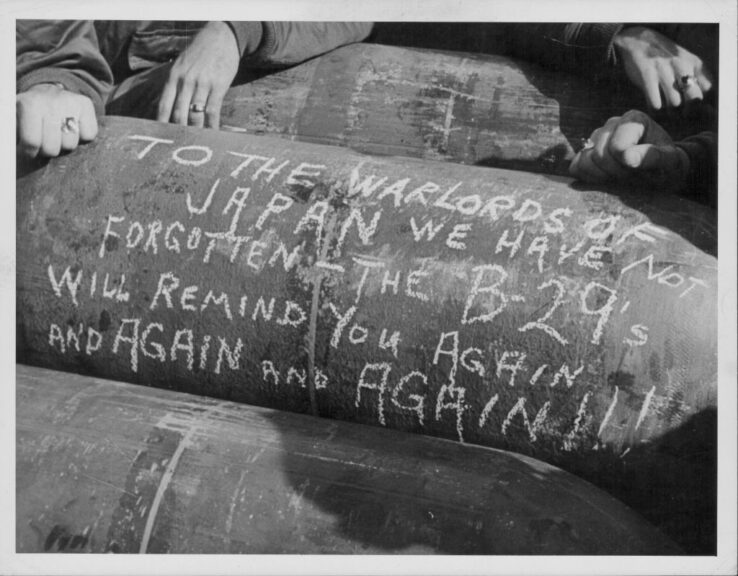

With the Marianas in the central Pacific just 1,200 miles southeast of Japan, both sides understood the significance of the upcoming battle for Saipan, the first of three islands in the chain slated for capture (the other two being Guam and Tinian.) For the Americans, taking the Marianas would pierce the inner ring of the enemy’s island bastions in the central Pacific that currently barred the maritime approaches to Japan’s home islands. Not only could they establish a base of operations for further penetration of Japan’s defenses, but from Saipan’s three airfields Dai Nippon would suddenly be in range of the newly developed B-29 Superfortress bombers — a grim prospect for Tokyo.

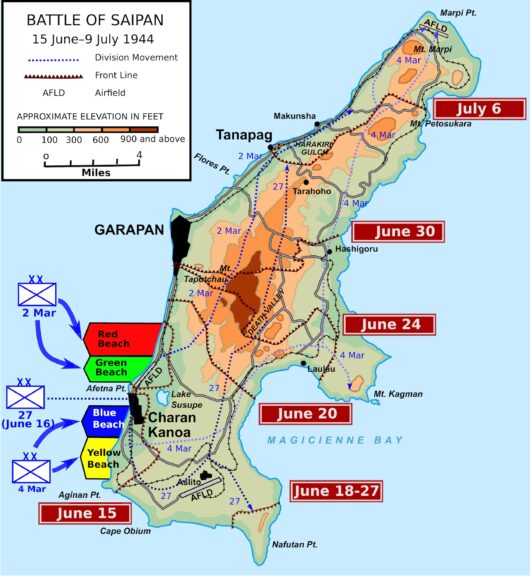

Map of the Battle of Saipan, June 15-July 9, 1944. Wikimedia Commons.

This would also be the first time in the war wherein a battlefield would be on Japanese soil, inhabited by Japanese civilians. Should Saipan fall, it was clear that Tojo Hideki’s militarist government would fall with it. For the Japanese High Command, the Marianas had to be held at all costs. With both sides coveting this immensely strategic island chain, the stage was set for one of the most brutal battles of the war so far, as well as trigger the largest carrier-versus-carrier naval engagement in history.

As would be the case with so many island landings, the pre-invasion bombardment did not obliterate the Japanese defenses as hoped. After hurtling some 15,000 16-inch and 5-inch shells, as well as over 165,000 smaller caliber ordnance during the three-day barrage, a formidable remnant of the emperor’s 31,000 troops managed to survive.

US Marines write a message on the side of a bomb … during the Pacific Campaign of World War Two, Saipan, circa 1939-1945. (Photo by European/FPG/Getty Images)

As the first wave of landing craft carrying 8,000 Marines chugged up onto two separate beaches, they were compelled to charge through a deadly torrent of shells and bullets, from pre-sited artillery and mortars to small arms fire coming at them from the Japanese first line of defense in the trees lining the shoreline as well as hills behind. The reason for the landing’s deadly reception despite the intense shelling was the topography of the island. As the overall invasion force commander Marine Lt. Gen. Holland M. Smith warned before the operation commenced, “We learned how to pulverize atolls. But now we’re up against mountains and caves where the Japs can dig in. A week from today there will be a lot of dead Marines.”

The first wave of Marines from the 2nd Division of the U.S. Marine Corps reached a beach of the island of Saipan (Marianas, central Pacific), June 15, 1944. Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Smith was right. Veteran John C. Chapin described the chaotic and bloody scene that morning as U.S. Marines hit the beaches under murderous fire. He would never forget “Bodies lying in mangled and grotesque positions; blasted and burned out pillboxes; the burning wrecks of LTVs [landing vehicles]…the acrid smell of high explosives; the shattered trees; and the churned up sand littered with discarded equipment.” By the end of the first day, Smith put 20,000 Marines ashore, but at a cost of 2,000 dead and wounded.

During the first night, the Japanese Army commander, Lt. Gen. Yoshitsugu Saitō, launched a series of sporadic attacks that failed to dislodge the Marines from their tenuous foothold on the island. The following day, having learned from the Navy that a potential sea battle was in the offing, Smith ordered his reserve Army battalions off the ships and into action to shore up the Marines’ perimeter.

Imperial Japanese Army Lieutenant General Yoshitsugu Saito. The Asahi Shimbun. Wikimedia Commons.

As night fell on June 16, D+1, the determined Saitō vowed again to drive the Americans off his country’s sacred soil and back into the sea. Just before 4:00 AM, alert Marines heard the rumbling of engines and metallic clanking of tank treads. To their shock, the largest Japanese armored attack of the war — some 44 tanks with 1,000 elite assault troops — came crashing into their line. The disciplined Marines at whom the attack was aimed methodically deployed anti-tank guns, bazookas, machine guns and rifles to wipe out the Japanese assault. At daybreak the exhausted defenders beheld a ghastly landscape littered with the burned out hulks of at least 24 tanks and hundreds of Japanese bodies. Once again, Saitō had failed to drive the hated enemy off the island.

On D+2 the landing force began to push inland towards the Japanese holed up on the central and southern parts of the island. As the U.S. troops made their way south to Aslito Airfield, they had to move through head-high sugar cane that offered an enemy already expert at concealment a target-rich environment. Unable to make out anyone on either side in the thick vegetation, U.S. troops were being shot down, sometimes at point blank range by hidden Japanese just yards away. Flamethrowers were brought in to spray the cane fields with terrifying liquid fire. The flushed out Japanese were then picked off in, as one Marine described it, “a real rabbit shoot.” Americans were finding Saipan to be not so much an island paradise as a suffocating nightmare as casualties mounted.

The fighting for Saipan quickly degenerated into a type of cruel, medieval contest fueled by the abject hatred between the Americans and their Japanese tormentors. No quarter was given, nor expected. The Marines and Army had already learned from previous fighting on New Guinea, the Solomons and Gilberts that the Japanese, for whom being taken captive was a disgrace, often feigned surrender, only to kill the lulled Americans with concealed pistols or knives or by blowing their would-be captors, and themselves, to bits with hidden grenades.

Charan Kanoa, Saipan after the battle of Saipan in June-July 1944. Image shows the effects of bombardment on town. Taken from Philip Crowl’s “Campaign to the Marianas,” published by the Center for Military History, U. S. Army. Originally in Department of Defense files.

As such, the Americans moving off the beach were understandably wary of entering narrow caves, barns, huts, and rubble within the destroyed town of Charan Kanoa in which there might be nothing or an enemy soldier waiting to take one more American with him before his death. They were taking no chances, sometimes with tragic results. Marine William Rogal remembered after losing a man shot by a Japanese hidden in a hole, they opted to just toss a grenade in first from then on. “Unfortunately, the next one was occupied by a bunch of school girls. Little Chamorro girls in there. That was really a sad, sad thing. But I guess that’s the kind of thing that happens in war.”

Despite fierce Japanese resistance, Aslito was soon in U.S. hands. Once secured, the Seabees (Construction Battalion) went to work to smooth out the runway and establish a bona fide airbase. By D+8 a squadron of powerful, heavily-armed USAAF P-47 Thunderbolt fighters of the 19th Fighter Squadron would be flying from the airfield to add lethal firepower to Naval close air support as the battle spread out across the island.

As the Marines and soldiers continued the fight, their stress was heightened even more when at dawn on June 19, D+4, they looked out to sea and saw nothing but an empty horizon where the night before a mighty flotilla had been at anchor. The ships had all gone. No doubt many troops on the island anxiously harkened back to August 1942, when the U.S. Navy had for a time abandoned the 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal to fend for themselves after the mauling it received at the hands of the IJN in the naval battle of Savo Island. Had something similar taken place during the night out there? Were they alone, marooned on this island of death? Said Marine Herbert Newman, “It was pretty leery when you look out there in the ocean and there’s no ships. There wasn’t a ship in sight.”

But where had they all gone?

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities trader, columnist, and author of two acclaimed novels. Along with Daily Wire, his articles have appeared in the Wall Street Journal, New York Daily News, New York Post, National Review, The Federalist, The Hill and other media outlets. His newest book, LIFE IN THE PITS: My Time as a Trader on the Rough-and-Tumble Exchange Floors, is a fun and informative memoir of his time as a floor trader in Chicago and New York. You can also find more of Brad’s articles on Substack.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.

Continue reading this exclusive article and join the conversation, plus watch free videos on DW+

Already a member?